Most people try to avoid thinking about death, but for some, it becomes their life’s work. Funeral directors and morticians spend their lives surrounded by death, while also offering comfort to the living. Throughout history, funeral directors have played vital roles in their communities, both in Delaware and across the nation. However, the history of the American death care industry, Delaware’s included, is complex. The care people and their loved ones received varied widely based on a range of factors.

Before industrialization, most deaths took place at home. Caring for the deceased was a deeply personal, family-centered process. Friends and neighbors would come to help the grieving family, often led by women who had participated in similar efforts. Local cabinetmakers built simple coffins, and after a service in the home, coffins were carried to the gravesite on foot (History of American Funeral Directing). If the deceased was a landowner, they might be buried on their own property.

Over time, skilled tradesmen, such as carpenters and sextons, began to play a larger role in the funeral process. Many expanded their businesses and adopted the title “undertaker.” Carpenter-undertakers offered a line of pre-built coffins and coffin accoutrements, and some added transporting the coffin by cart to their services. Women were still part of the process, but their duties of cleaning bodies and wrapping them in shrouds became less visible as the profession formalized, an imbalance that persisted well into the twentieth century.

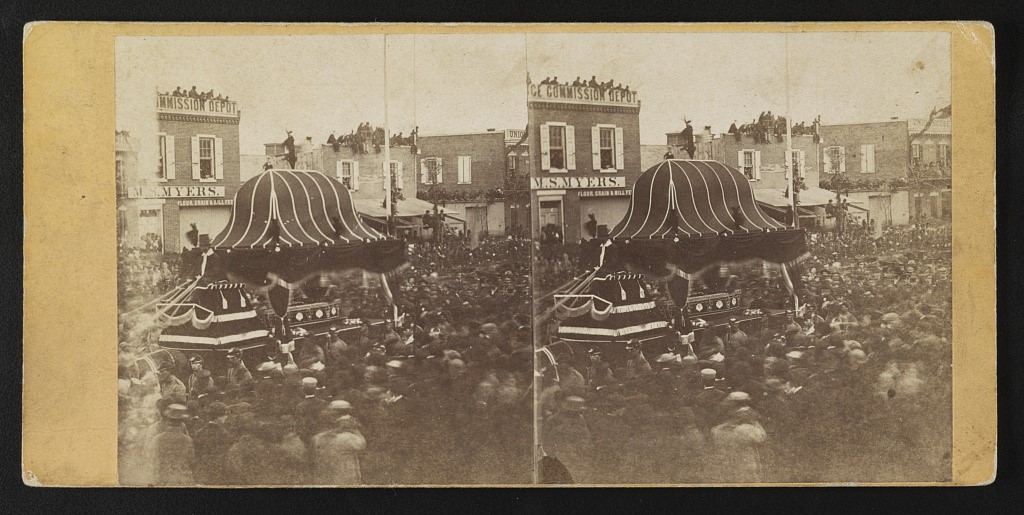

Undertaking began to change in the late 19th century, due to a variety of factors. One major development was the acceptance of embalming, which became increasingly common during the Civil War. Embalming was used to preserve the bodies of many soldiers as they were transported back to their homes for burial, and it famously prepared President Abraham Lincoln’s body, which was paraded around for weeks after his assassination.

As cities grew, cemeteries were established farther from populated areas, creating an increased need to transport bodies to gravesites. Carts became funeral coaches, which evolved into horse-drawn funeral carriages, which were eventually replaced by motorized hearses. Catalogs offered a range of coffins and accessories. The once home-based funeral became a business, often conducted in funeral parlors.

Of course, not everyone experienced death care in the same way. During the Antebellum period, enslaved people were often denied marked graves or formal burial rites. When possible, families and communities gathered at night to honor their loved ones, often at the edge of the plantation, blending African spiritual traditions with Christian practices. These ceremonies were not only acts of mourning but also of celebration and resistance, symbolizing freedom beyond life.

During the Reformation, the paths of Black and white undertaking converged, but by the 1870s, Jim Crow laws were being established across the United States. In some places, both Black and white undertakers received the same training, but in most states, white undertaking and Black undertaking developed as separate, yet parallel, industries. While segregation limited clientele, Black funeral directors became important community leaders and business owners. Many used their success to fund mutual aid societies, sponsor education, and support the civil rights movement.

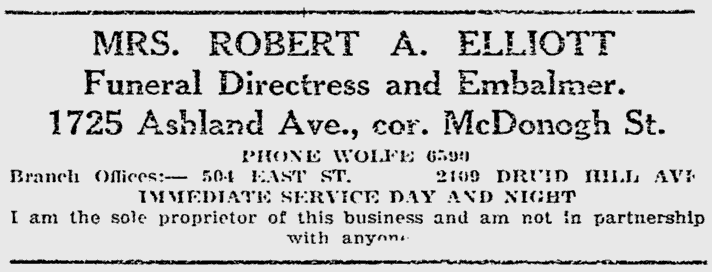

Men were not the only ones in charge of these businesses. During the 1915 convention of Booker T. Washington’s Negro Business League, George W. Franklin, president of the National Negro Funeral Directors Association, acknowledged the growing field of African American funeral directors, with “over 1,100 men and women actively engaged in the business” (To Serve the Living). As history was recorded, the achievements of Black women in death care were overlooked. Dr. Kami Fletcher, a professor of Africana studies who focuses on death care, suggests it may be because “Booker T. Washington was more focused on promoting the Negro Business League because it showed this respectability, in particular the ability of Black men to adhere to gendered norms of the breadwinner” (Hidden in Plain Sight).

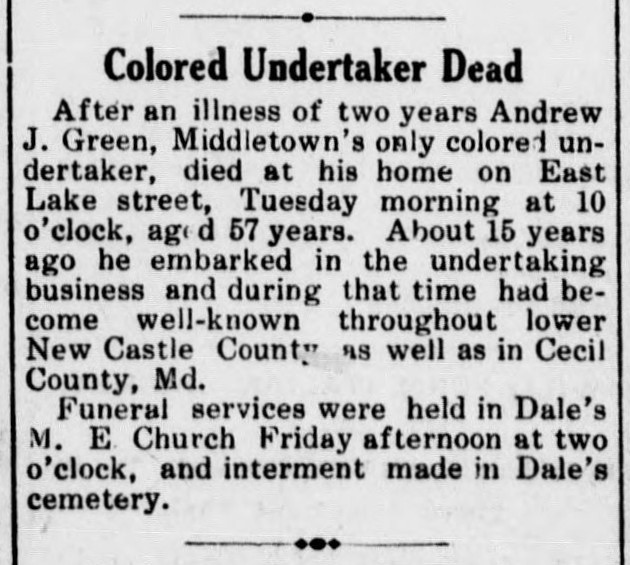

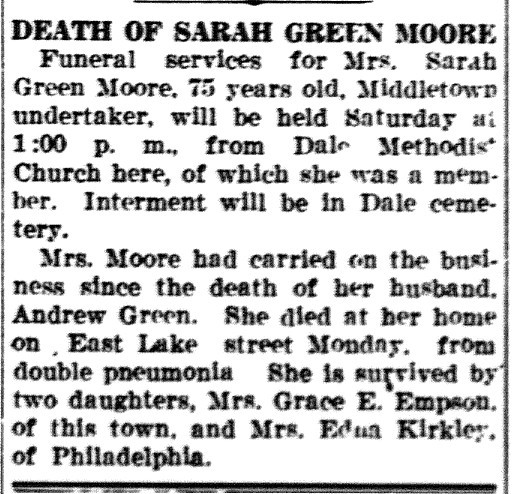

Delaware had its own pioneering Black female undertaker. Sarah Green Moore began her career as a funeral director while assisting with her first husband, Andrew Green’s, undertaking business in the 1910s. They were the only Black undertakers in Middletown, Delaware, and served not just northern Delaware but also nearby regions of Maryland and Pennsylvania. When Andrew passed away in 1922, Sarah took over the business and continued her work in death care until her passing in 1939. At the time of her death, she was owed $1,300 for her funeral services, roughly equivalent to $30,000 in 2025.

Since Sarah Green Moore’s time, funeral homes have continued to evolve, but many traditions remain familiar. Families still rely on funeral directors to prepare loved ones, organize services, and provide transportation to final resting places. Yet, as the cost of living (and dying) continues to rise, there have been some changes in consumer spending. More Americans are seeking alternatives such as cremation, natural burial, or donation to science.

Only time will tell how these choices will shape the future of the funeral industry. What remains constant is the compassion and care at the heart of this work.

By preserving the records, photographs, and stories of Delaware’s funeral professionals, the Delaware Public Archives ensures that the ways we honor the dead continue to tell us something profound about the living.